Caught between sides: "Owning a truck is what killed my grandfather"

Mª Guadalupe Palau grew up with stories shrouded in half-truths. One grandfather, she was told, died naturally of asthma, while the other passed away in prison. “They killed him, but you mustn’t say that. When someone asks about your grandfathers, just say they died and leave it at that,” her family would caution. It wasn’t until years later that Lupe uncovered the startling truth: “Owning a truck is what killed my grandfather.”

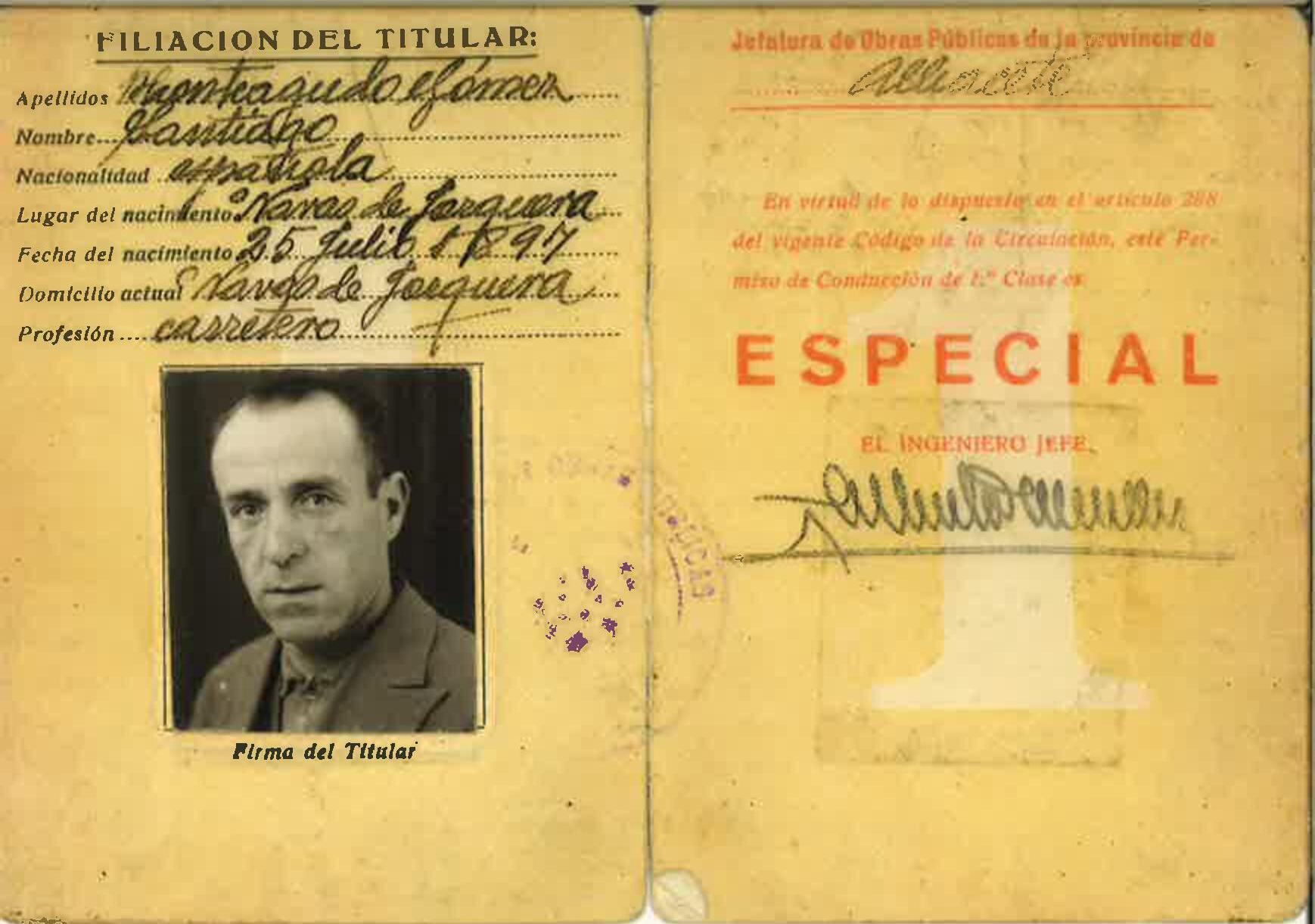

Santiago Monteagudo Gómez was born on July 25th, 1987 in the peaceful village of Navas de Jorquera, nestled in Albacete, Spain. A hardworking man, he supported his family by transporting goods to northern Spain in his modest truck. His wife, Felisa García Soriano, born February 12, 1902, ran a small shop in their village. Together, they raised six children —Andrés, Hipólita, María Catalina, Santiago, Segundo, and José— and built a life of stability and quiet ambition. That life, however, would unravel when the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) tore through the nation, pulling even small, remote villages into chaos.

The Albacete province remained under Republican control throughout the war, avoiding the direct domination of Franco’s Nationalist forces. But the local power vacuum created its own dangers. During the early months of the conflict, revolutionary groups associated with leftist parties and unions took control. These groups, emboldened by the absence of central authority, targeted anyone they considered an enemy: landowners, clergy, aristocrats, and suspected fascists. The lines between politics, class, and personal grievances blurred, and accusations often stemmed more from vendettas than ideology.

Santiago Monteagudo was one such victim. According to his granddaughter, neighbors in the nearby village of Madrigueras accused him of being a fascist —not because of his beliefs, but due to old grudges. Arrested by Republican forces, he was imprisoned. “My grandmother would walk to the nearby village to bring him food,” Lupe recounted. “I don’t know what trial they gave him, but they released him eventually, saying, 'This man is not a fascist'”.

Santiago's driving license, provided by his granddaughter, María Guadalupe

Freedom, however, did not bring safety. Santiago’s truck, once a symbol of his hard work and livelihood, had become a liability. In a time when resources were scarce, owning something as valuable as a vehicle painted a target on his back. “Then came the other problem with the truck,” Lupe explained. “That was the cause of his misfortune and death”

At dawn on August 30, 1936, republican militiamen stormed into Santiago’s home and ordered: “Santiago, get the keys and get in the truck.” He was forced to drive towards Albacete, transporting seven people —acquaintances, relatives, and friends he knew well. Along the way, they made him stop and ordered the others to get out. “They were going to kill my grandfather too,” his granddaughter recounted, “but one of the militiamen said, ‘Leave him, he hasn’t done anything and has six children, let him go.’”

The tragic fate of those who weren’t so fortunate that night is detailed in the Causa 348-39 (Casas Ibáñez), recorded in the Spanish Archives Portal (PARES), which confirms what his granddaughter had said. Around midnight, several men from Navas de Jorquera were taken: Segundo del Egido Monteagudo, José Manuel del Egido Gandía, Superio Peñaranda Teruel, Octavio Peñaranda Gómez, José María Juncos del Egido, Gracias Gandía Garrido, and Severiano Gandía Alfaro.

Three days earlier, on August 27, 1936, the fates of these men took a dire turn. Republican militiamen Teodosio García Escribano and Gabriel Penaranda Cebrián had detained them and led them to the committee of the “ill-fated Popular Front” —the coalition of left-wing parties that had won the last elections of the Second Republic on February 16. They remained confined until the 31st of that month, when they were taken out and transported in Santiago’s truck.

About five kilometers from the village, the document states, they were “vilely murdered” —their bodies, presenting bullet and stab wounds when found. They were then loaded back onto the very same truck Santiago had driven earlier that night and taken to the Júcar River. There, at the Presa de los Frailes, they were discarded into the water, a grim attempt to erase their existence. The following day, when the corpses were discovered floating downstream, they were retrieved and, once again using the same truck, taken to a small mountain known as “Monte Rubio,” where they were abandoned.

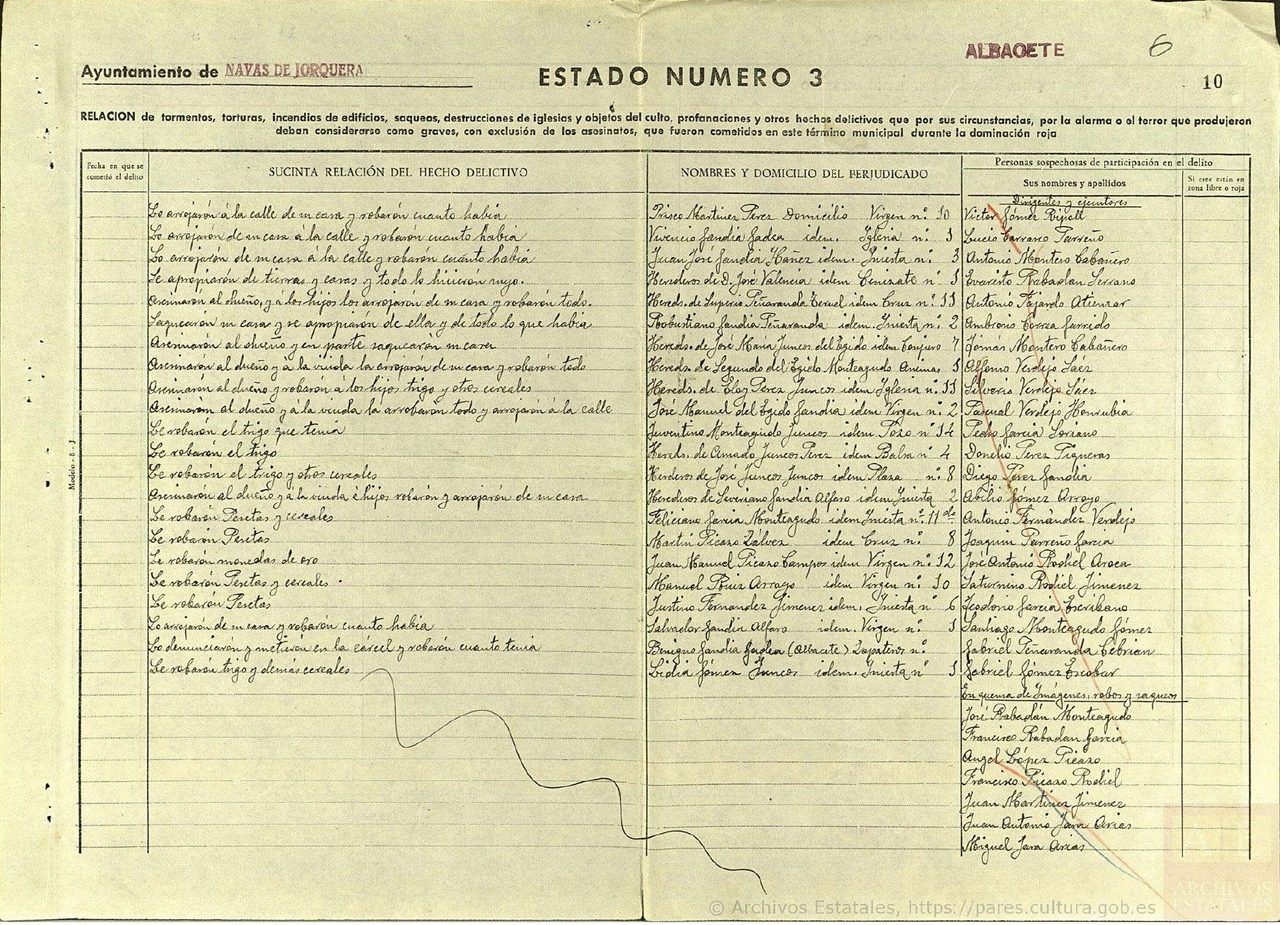

Later, in the same report, under the heading “responsables,” a list of individuals implicated in the deaths, arson, and theft includes the name of Santiago Monteagudo López, appearing second to last in the second column—an eerie and unintentional connection to the events that unfolded that tragic night.

Picture of a firing Squad. Retrieved from Castilla la Mancha's democratic memory project

After being missing for three days, Lupe’s mother, waiting anxiously at the door, saw her father Santiago “walking like a living corpse.” He spent a week in bed, unable to speak or recount what had happened. “Someone who was like the village doctor”, as his family recounts, had been called to treat him. According to Lupe’s mother, they performed sangrías (bloodletting) and placed sanguijuelas (leeches) on him as treatment. Little did Santiago know that that night would haunt him and ultimately ruin his life. The horrors he endured would leave a lasting mark, not only on him but on his family as well.

Once the war ended, the accusations from the families of those executed became relentless. Amid this turbulent aftermath, Franco’s regime (1939-1975) intensified its use of summary trials, or “juicios sumarísimos,” which had begun in March 1937, governed by the Military Justice Code. These weren’t just legal proceedings —they were spectacles of swift and brutal justice, designed to stamp out any flickers of opposition. It was within this oppressive system that Santiago found himself entangled, accused by neighbors driven by old grudges and the chaotic fervor of the times, linking him to the tragic deaths.

Picture of San Gregorio church, Navas de Jorquera, Spain. Retrieved from Digital Library of Albacete

This arbitrariness is starkly evident in the Causa 348-39 (Casas Ibáñez), a document that not only lists Santiago as a suspect in the murders but also accuses him of a litany of other crimes: “torture, building arson, looting, destruction of churches and religious objects, desecrations, and other crimes.” The charges painted a harrowing picture of retribution. For instance, the same document recounts that José Manuel del Egido García, a resident of Calle Virgen No. 2, was murdered, and his widow was subsequently stripped of everything and thrown onto the street.

The accusations were not without errors, adding a layer of absurdity to the injustice. In the 1941 statements collected from the aggrieved parties, Santiago’s name appears with an incorrect second surname, García instead of Gómez. One accuser, Dº Celio Juncos Gandia, aged 28 and the son of Don José María Juncos del Egido, claimed that the victims were transported in a truck owned by his own father, Mr. Juncos—a detail that deepened the confusion surrounding the case.

Document stating that Santiago is guilty and naming his crime. Retrieved from PARES

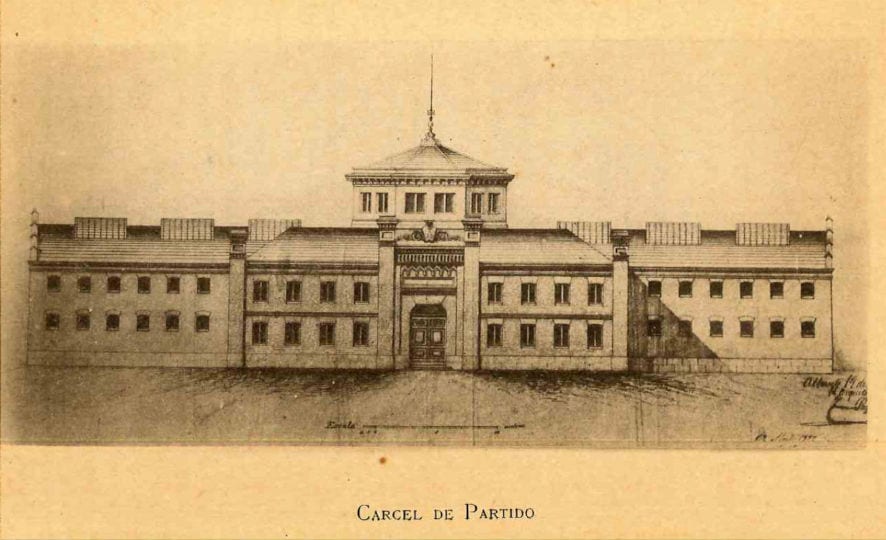

On June 22, 1939, after an undoubtedly biased War Council, Santiago was sentenced to death. Condemned, he was taken to the Albacete prison, while his family left everything behind in their village of Navas de Jorquera to be with him. For three long years, his wife Felisa and her eldest son desperately sought support, but, as Lupe recalls, “everyone was afraid of reprisals,” leaving them to face their struggle alone.

Santiago's family and friends, like countless others, tirelessly penned pleas for mercy. These documents, signed by the accused and their supporters outside prison walls, were heartfelt attempts to humanize the prisoners and distance them from the image of a uniform enemy. They aimed to paint a picture that aligned with the regime's ideal of a “person of good and order.”

“The three years my grandfather was in prison, they were without any information about the trial, unable to do anything”, recalls his granddaughter. During that time, Santiago wrote letters to his family, recovered by Lupe over the years, in which he tirelessly proclaimed his innocence:

Picture of Albacete Prison. Retrieved from Castilla la Mancha's democratic memory project

...Juan Jose Gandía, Juventino, and the mayor, they all know I am not guilty of anything. ...I was almost a victim like they were, which God did not allow. ...If I couldn’t prevent it, it was not for lack of trying, for which I almost lost my life, although it’s not recognized, this is the truth.

Felisa suffered multiple losses: part of their land confiscated, their house requisitioned, and fields poorly sold. Years later, while Lupe helped her empty the house they had in Albacete, she discovered an old spool of thread in a forgotten corner. When she opened it, she found a hidden letter written by her grandfather from prison. In it, he once again proclaimed his innocence:

…because I have nothing to fear because I have always been honest… an injustice is being done to me.

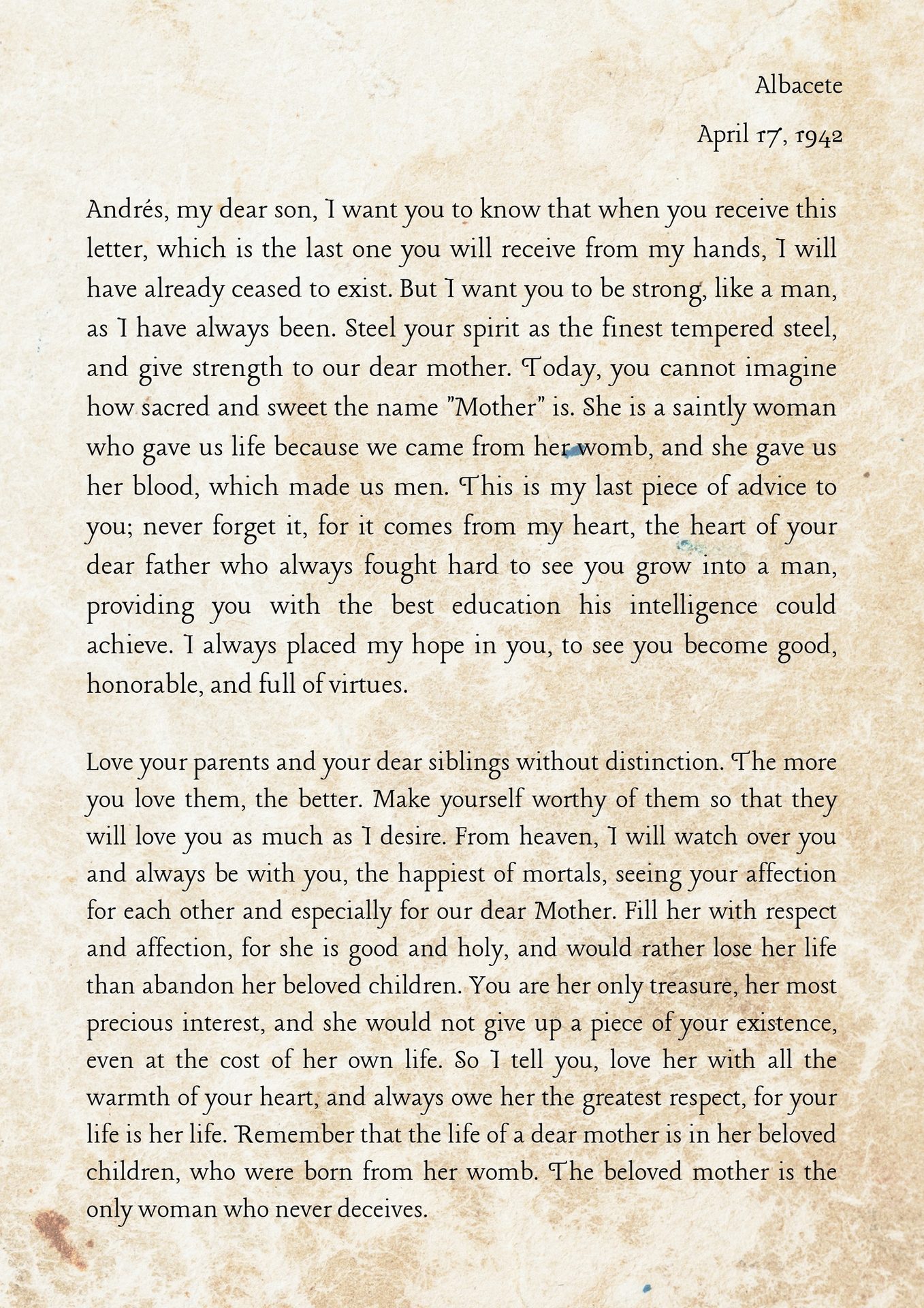

Nothing and no one could save him. A prison guard alerted his two eldest sons that their father was set to be executed on August 12, 1942. Four months earlier, on April 17, Santiago had penned his final letter to his son Andrés, the last one they would ever exchange:

…when this reaches you, I will no longer exist... Goodbye, dear wife, goodbye, dear children of my heart, and receive my last kiss drenched with the blood of my heart…

Andrés and Hipólita arrived at dawn, retrieved their father’s body on a cart, and buried him in the Albacete cemetery. Years later, in 1981, they exhumed and moved his remains to a niche. Although the custom on All Saints’ Day is to bring flowers, his wife Felisa “never went to the cemetery.”

“I didn’t know where my grandfather was,” Lupe recalled. “I asked my cousins, and they accompanied me. For me, it is important to know that he is there… That’s the most important thing, to be able to close wounds.”

As Lupe grew older, her curiosity about the past only deepened. She would often ask her grandmother Felisa about the war —pressing her to explain who were the good guys, who were the bad, and what had truly happened. Felisa, however, always gave the same weary answer: wars are bad, and both sides are to blame. “They ruined my life,” she would say. Her perspective was shaped not by ideology, but by the profound pain of loss and upheaval.

“Thousands of families were torn apart, dreams shattered, people disappeared,” Lupe reflects. “It’s not just the person who is killed or the one who survives. It’s the thousands of families who can’t live the lives they were meant to live.”

“All lives are broken,” she concludes.

Picture of Santiago's Grave. Provided by his family

Santiago's last letter to his family

Translation of Santiago's last letter to his family, original text provided by the family. Translated by our team

A republican matriarch: Josefa's jouney

Dolores, a short but strong tempered woman now in her 60s, puts on the same long coat she has been wearing since her university years 4 decades ago in the Andalucian city of Granada, Spain. She now lives in l’Alfàs del Pi, a small town in Valencia next to the warmth of the Mediterranean Sea. It is located 5 hours away by car from her birthplace, the small but incredibly historic Arjona, in Andalucia. She’s getting ready for work as a civil servant in gender affairs in the town hall just a few minutes away by foot from her place.

Dolores (a name that translates literally to ‘pains’ in English) puts on her sunglasses and heads out the door. Her university studies in philosophy have prepared her well for the continuous fight in favor of women’s rights. She’s always on the lookout for gender biases, which she will not hesitate to debate when needed. She was not raised to be silenced. Her family had already suffered too much for her not to defend her ideals.

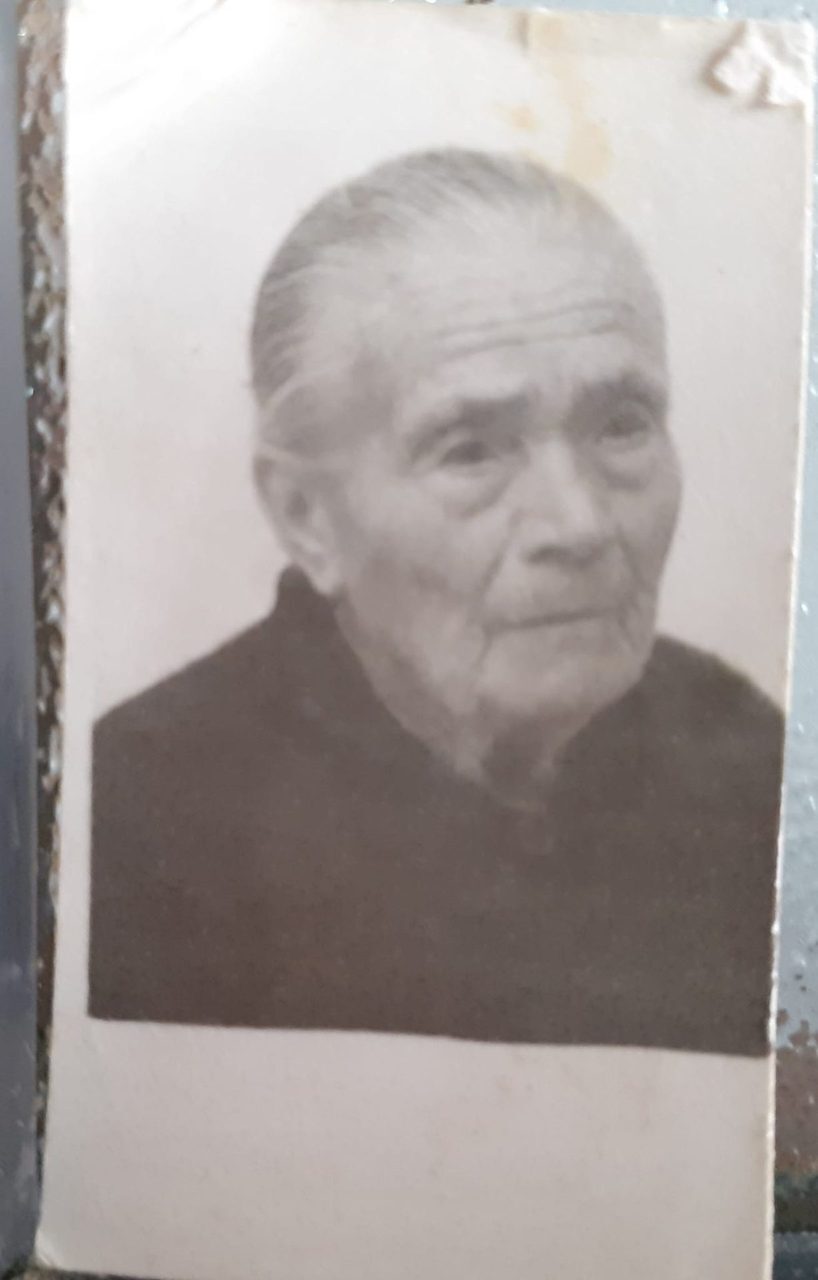

As she walks down the road towards the center of the town, she thinks of her grandma Josefa. It’s been over 40 years since she died, but her image is always present. Josefa was a busy woman, she could never stay still, wandering around town, buying, selling, talking, holding one of her granddaughters with one arm and carrying a basket with the other, always wearing the brown colors of Our Lady of Mount Carmel’s habit (Nuestra Señora del Carmen) whom she prayed to with fierce devotion.

Dolores often thinks of her grandma Josefa on her way to work because, without her grandma’s resilience, her family might have crumbled entirely. Dolores and her sisters, the first ones to ever go to university in their family, feel the need to continue Josefa’s fight, who had been handed a weak hand in the game of life, but her determination had kept her and her family alive.

Like Dolores and her grandma Josefa, many families in modern Spain continue to be deeply impacted and scarred by the events that unfolded during the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) and the Francoist Dictatorship (1939-75). Most of the people that lived through those troubling times are now dead, and many others are getting too old, risking all these personal experiences and traumas to completely disappear from the modern imaginary.

Preserving these family stories sheds light on narratives that were neglected, erased, and silenced by the Spanish government for many years. It is only until recent decades that many archives from those times have been made public and that the living members of those families have tried to recover information they thought to be long lost. These personal narratives have been passed down orally through generations. The generational trauma continues to live in the collective memory of each family and of the country as a whole. This project attempts to preserve these family stories and to emphasize the importance of addressing the open wounds left by the careless destruction of war.

Josefa's ID. Provided by her family

story

This is

Josefa Arazola Sánchez was born into a humble Andalusian family on January 20, 1898. She spent her early years working the field, harvesting olives and chickpeas, learning how to work the crops, an ability that would help her throughout her life. As a rural woman of her time, going to school was never a priority and sometimes, not even an option. She never learnt how to read or write, but no one ever questioned her knowledge when it came to the farmland, especially if it had to do with olives.

Her granddaughter, Dolores, recalls Josefa as a “very petite woman; not much physically to her, but very, very strong”.

She was born in Arjona, a small, ancient town in Jaén, Andalucía. A region where olives have flourished for over 12 000 years. The Phoenicians, the Iberians, the Romans, and the Muslims all worked in one way or another with this essential ingredient of the Mediterranean identity. The never ending sea of olive trees was witness to Josefa's entire life.

It is precisely among the olive groves where she met her life partner Manuel Álvarez García. She was 13 and he was 23. An age gap that was slightly problematic even then. Josefa’s family did not approve of the relationship due to her young age, and Manuel’s family looked down upon Josefa due to her social class. Manuel belonged to a household where everyone knew how to read and write, and which was always involved in the public life of the town.

Picture of women harvesting olives in Arjona. Retrieved from Arjona's Town Hall.

Despite the complexities of their relationship, they eventually got married. She was 19, he was 29. In her later days, Josefa told her granddaughters the story of their wedding day. She often told them with a nostalgic smile, that when the ceremony was over, he took her in his arms and said “Now you’re mine”.

That same year, 1917, they welcomed their first born, Manuel.

Dolores, Manuel Jr.’s daughter and Josefa’s granddaughter, emphasizes how, in those days, it was not uncommon for women to have numerous children, many of which ended up dying. Manuel Sr. and Josefa had 10 children, only 5 of them survived. 2 men and 3 women: Manuel, Francisca, Josefa, José, and Juana.

In 1931, the Second Spanish Republic began. The local Socialist Group of Arjona had already been formed before 1931. Later, in 1936, at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War, Manuel Sr. was appointed councilor of the local government, which was led by the democratically elected Spanish Socialist and Workers’ Party (PSOE).

The province of Jaén remained loyal to the republican cause throughout the war, and Arjona, with its socialist government, was no exception. When the war began, many local villagers broke into the luxurious family crypt of one of the wealthiest landowners of the town, the Baron of Velasco. They took his mother’s remains as a symbol of the fall of the aristocracy and of the right wing.

Meanwhile, Josefa’s eldest son, Manuel Jr., who was almost 20 years old at the time, enlisted voluntarily in the Republican Front’s army.

Josefa was a woman who took matters into her own hands. Her granddaughter, Carmen, emphasizes her “strong and determined character”. The war period only toughened her up.

Picture of soldiers of the Republican band. Retrieved from RTVE

Picture of kindergartner in Catalonia, around year 1936. Retrieved from BNE

Despite the danger of the situation, she would sometimes go to visit her son in the battlefront. Losing him was one of her biggest fears. She prayed for her son to be safe, and promised Our Lady of Mount Carmel (Nuestra Señora del Carmen) to dress faithfully in her habit if Manuel Jr. came back. When he finally returned safe and sound, she kept true to her word and wore the habit throughout the rest of her days.

The republican cause stood in favor of the separation between the state and the Catholic church. This sentiment was quite strong among the families that supported the Spanish Republic. Josefa, a strong supporter of the Republic, was raised Catholic. Despite the war, her beliefs remained untouched.

Picture of the celebrations of "La Virgen del Carmen" in Andalucia, Spain. Retrieved from Agenda Cultural de Andalucía.

In late March, 1939, loyal Republican provinces including Jaén were taken by the Francoist troops, leading to the end of the Spanish Civil War.

This marked the beginning of Franco’s military dictatorship which lasted until his death in 1975. The early period was defined by strong political and economic repression forced on those who opposed his movement. The francoist era was also linked to the ideological identity of the National Catholicism (nacionalcatolicismo) in which there was an open unity between the Catholic church and the true Spanish identity, which could only be embodied through the francoist government.

The town of Arjona, having been a strong supporter of the Republican side, as well as the rest of the province of Jaén, was heavily punished by the Francoist military.

The mayor of Arjona, Juan Pérez Laguna, fled to France and remained in exile till the end of his days. Meanwhile, Manuel Sr., having been a counselor of the local socialist government, was arrested. Later, on February 24, 1940, as part of the summary executions and trials that were foundational to Franco’s repression tactics, Manuel was sentenced to spend the rest of his life in prison in Málaga.

Picture of ruins in Madrid. Retrieved from RTVE

At the same time, Josefa’s son, Manuel Jr. who was enlisted in the Republican Front, was sent to Andújar as part of the mandatory military service installed by Franco’s regime. The implementation of this measure served the purpose of promoting and conserving the ideology of Franco’s dictatorship. The army, in this case, was the backbone of his system. Therefore, a military service in which young men were forced to participate became an indoctrination tool, and it was commonly referred to as ‘la mili de Franco’ (Franco’s military). Leaving the service was morally and legally frowned upon, and could lead to the direct imprisonment of the man in question. Manuel Jr. fulfilled 5 years in the military service, living in what his daughter, Dolores, recalls as inhumane conditions.

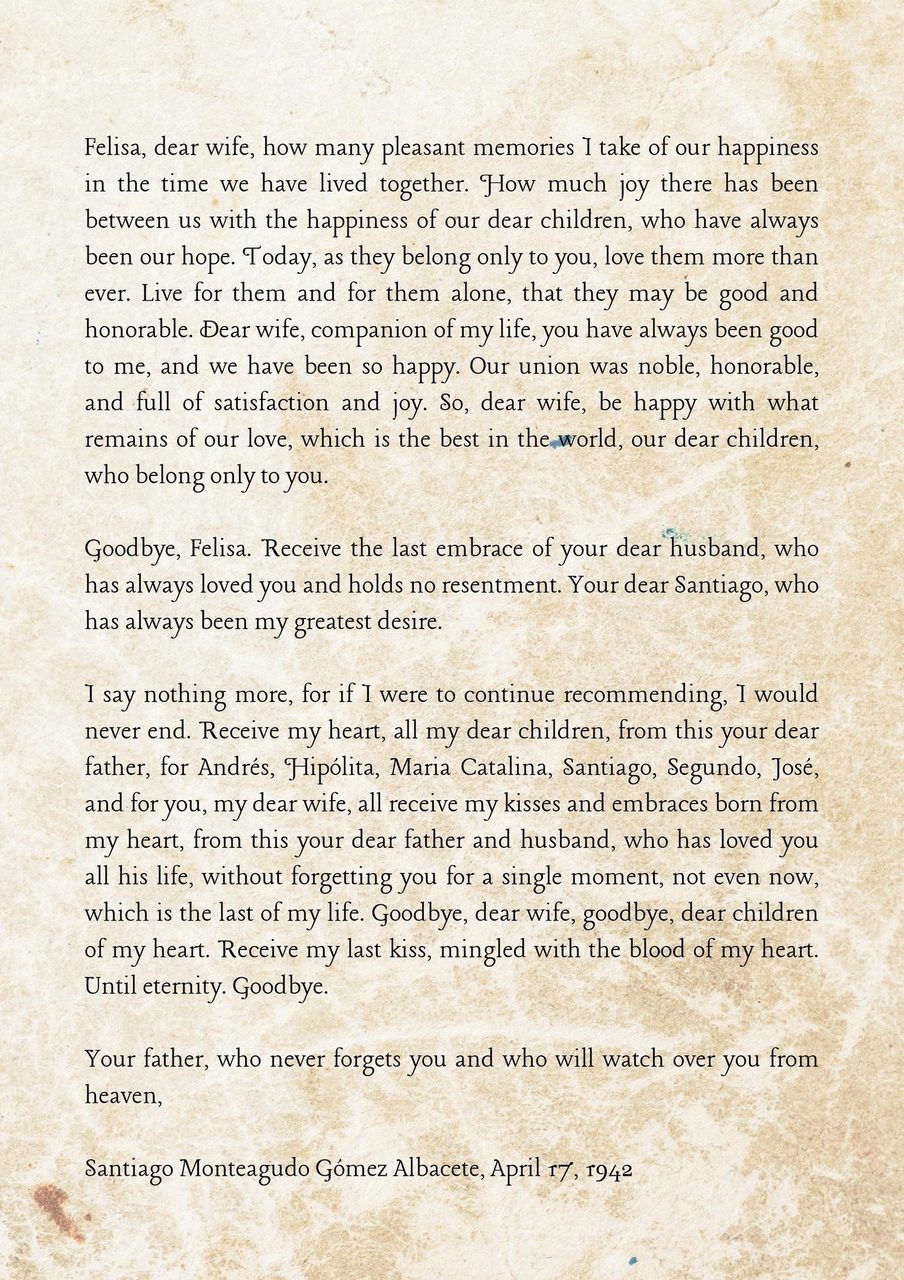

Without her husband and her eldest son, Josefa found herself alone in charge of her four children. She was witness to the political cleanse that took place in Arjona, and to the active punishments handled by the Francoist military upon the active members of the defeated Republican cause. As Josefa had not participated actively in the war, she was never disciplined directly. But she never forgot how the women who had openly taken part in the conflict were all completely shaved and exhibited publicly in town. An image that continues to hunt Josefa’s descendants.

Picture of soldiers. Retrieved from RTVE

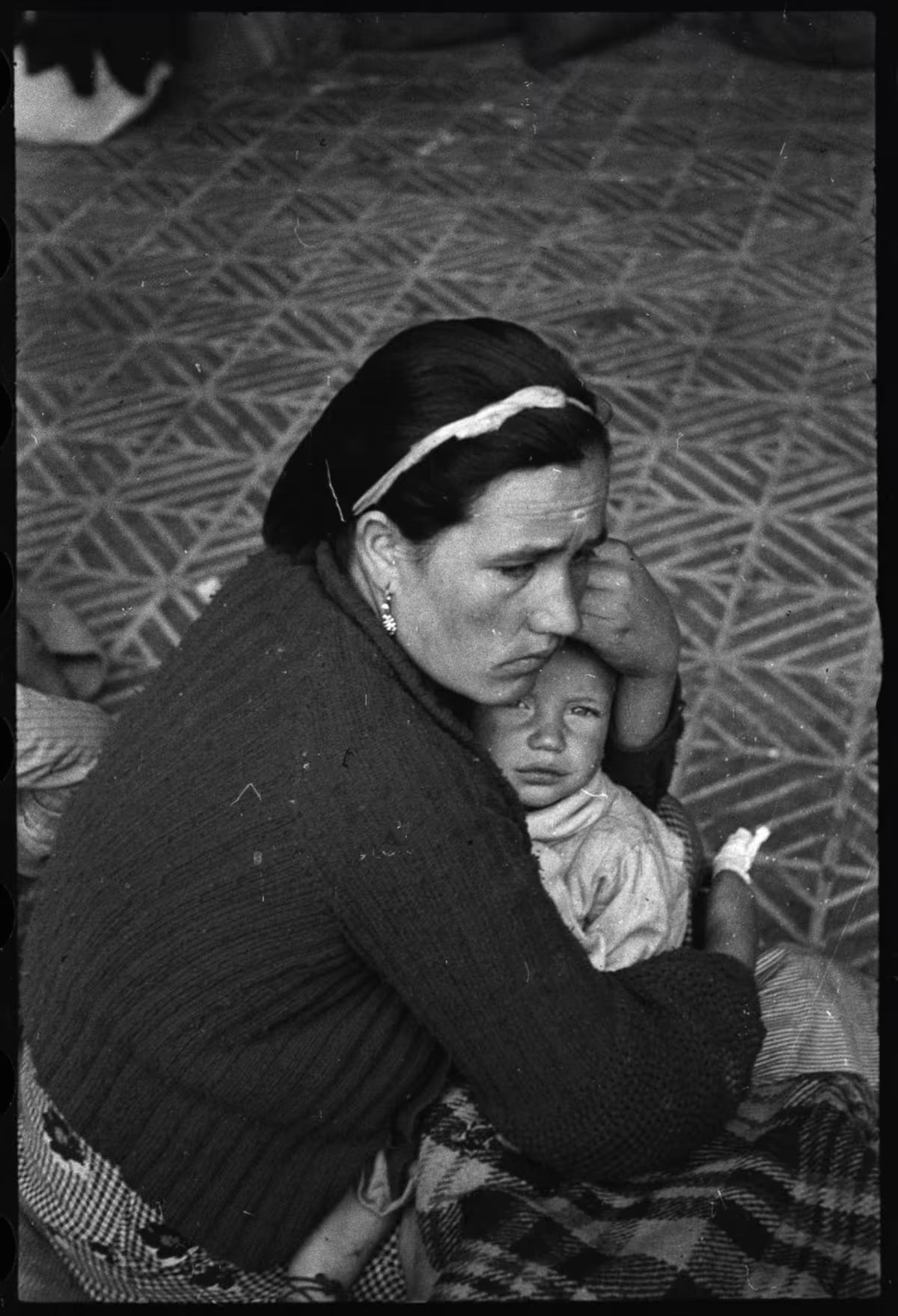

Picture of women after being punished. Retrieved from RTVE

Although it still has not been recognized as such, that first decade of Franco’s dictatorship was struck not just by scarcity, but by what modern experts have argued to be a full on famine. A catastrophe caused by the Civil War, the international isolation linked to Franco’s autarchy, and the terrible crops of those years. The scarcity was downplayed by the government at the time, but it stuck in the collective memory of many families, including Josefa’s, who barely made it alive.

Josefa did everything she could to survive during those years. She would wake up early and go around knocking on doors, offering work and help in exchange for food and money, anything that could help her and her children stay alive.

During those times of heavy scarcity, the government issued ration books to control the distribution of basic products like oil, chickpeas, and sweet potato. Josefa found a way to use these ration books as a trading currency, managing to get necessary goods and helping her family to survive.

Picture of the Estraperlo, the black market of the first years of dictatorship. Retrieved from RTVE.

Picture of Josefa. Provided by the family

The days grew longer and more tiring. Her eldest was still away, and her husband was still locked up. Josefa, as she often had to, took matters into her own hands. She approached many of the most influential landowners and aristocrats of the town, offered to work for free on their fields, and begged them to include her husband Manuel in the list of people whose sentences would be reduced. Her actions, alongside the need to get men to work on the harvests, led to Manuel’s release after 5 years of imprisonment.

With her husband back in the family, and Manuel Jr. starting his own family life with his wife Dolores, things finally began to stabilize.

The dictatorship left deep scars. Nearly half a million Spanish citizens went into exile. Close to 200 000 people died of malnutrition and other hunger-related issues between 1939 and 1942.

Picture of Carmen, Josefa's granddaughter, becoming mayor of Arjona. Provided by the family

With the turn of the decade, Spain began to re-establish its links with the international community. In 1953, Franco and the Vatican led by Pope Pius XII signed a concordat that defined and strengthened the relationship between the Catholic Church and the Spanish State. A month later, the US and Spain signed the Pact of Madrid in which they agreed on the construction of American military bases on Spanish territory in exchange for economic and military aid. These two agreements led to the reintegration of Spain to the West, an important development considering that the Francoist regime had stood with the Axis powers during WWII. In the 1960s, Spain began to experience brighter days, fueled by a new economic policy and the influx of foreign currency. This newfound wealth came from the growing tourism industry, remittances sent home by Spanish workers taking temporary jobs abroad, and contributions from those living in exile.

Neither Josefa nor Manuel spoke of the war or the early dictatorship. Absolute silence. No one mentioned it until the beginning of the Spanish democracy in 1978 after Franco’s death in 1975.

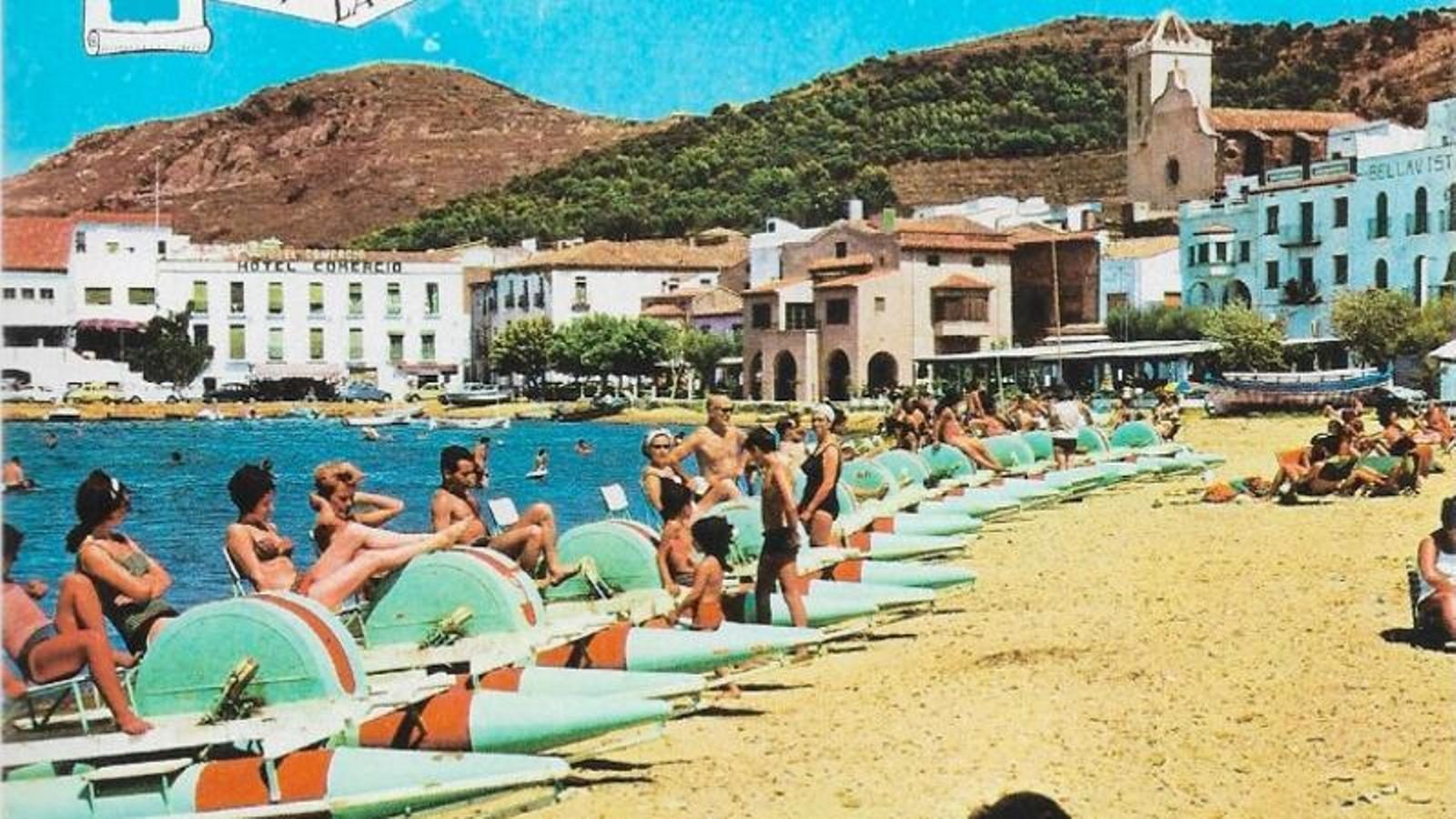

Picture of tourists in Spain during the dictatorship. Retrieved from Girona's City Hall

The weight of Josefa’s and Manuel’s experiences was passed down to their granddaughters who always felt the need to continue their family’s fights, both the republican cause and the gender issues. A legacy founded (maybe unknowingly) by Josefa’s feminist role. “We could say that our house was a matriarchy”, her granddaughter Carmen confirms.

The generation of Josefa and Manuel’s grandchildren lived through a very different era. They witnessed Franco’s death, the democratic transition, and the adoption of a new constitution. They no longer experienced scarcity, as the country underwent continuous development and increasing openness, with more labor rights and other advancements.

However, the political and gender awareness of their parents and grandparents remained strong, and they never had any regrets for being Republicans or “reds.” Josefa and Manuel’s granddaughters were the first in the family to attend university. “We have always been in constant revolution,” they say.

A toast was raised when the dictator died. The women of the family have continued the political struggle ever since.

Carmen, one of her granddaughters, entered politics and served as the Mayor of Arjona for seven years with the PSOE (the same party her grandfather had represented). When she expressed her desire to enter politics, her own family, still haunted by the trauma they had endured, warned her against it, saying they would shave her head and parade her through the town, just as had been done to many women years earlier at the end of the Civil War.

Another of her granddaughters, Dolores, continues to work today as a gender affairs civil servant in the town hall of l’Alfàs del Pi, in the Valencian Community. This highlights the importance of the gender values that Josefa, despite coming from a family with few resources and remaining illiterate all her life, managed to instill and cultivate within her family. Her legacy lives on.

Josefa passed away of old age on December 30, 1980, in a democratic Spain. She was buried in the habit she had promised to wear if God brought back her son alive. A final act of devotion that marked the end of her life’s journey.

From left to right: Dolores, Carmen, and Paqui, Josefa's Granddaughters. Picture provided by the family

Even now, her family speaks of her: always in motion, always giving. Her stories are shared at family gatherings, and the olives that saw Josefa’s story develop continue to nurture every meal of her descendants.

Her granddaughter Dolores and her two great granddaughters, both thriving young adults with university degrees, are back home for Christmas. Together with her husband, Ximo, Dolores has raised two independent thinkers, each exploring their paths while remaining rooted in the warmth of family. At the dinner table, as lively political debates reignite, a tradition as cherished as the holiday meal itself, Dolores observes her family with quiet pride.

In this moment, Dolores’s thoughts return to Josefa, whose strength carried the family through the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War. Dolores resolves not to take these special moments with her family for granted. She knows that a big part of her life is built on the foundations of her grandma Josefa, a woman who never gave up, even when all the odds were against her.

During Christmas dinner, with the chewed up olives as testament of the long night, the heated debates come to a momentary pause. The family stories take the spotlight, and Josefa’s great granddaughters relive her life and learn through each of the anecdotes that their mother, Dolores, tells with pride. Josefa lives on.

Picture of Josefa's family, her living grandsons, granddaughters and their partners. Provided by the family.

I don't need sponsors,

I surf better when I'm broke anyway.

Dave Parmenter Surfer

"A war between cousins and brothers"

That is how most Spanish people will still speak of the Spanish Civil War (if they speak of it at all). To most citizens, this war isn’t just another chapter in a history book, but a deep wound that has never truly healed. Due to the nature of the war, whether they had chosen to or not, cousins and brothers found themselves on opposite sides of a line that split families into two. For many, it is an episode that still lingers in our present lives, a legacy of division that has never fully disappeared.

For eight years, from 1931 to 1939, Spain lived under the democratic regime of the Second Republic. It was a period of time of fragile democracy, a short interlude of peace after the dark years of the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera. The red, yellow and purple flag hovered in the breeze, while the 1931 Constitution became the beacon of a new era, one filled with the promise of change. Public education for all, women’s suffrage and the beginning of a secular state were some of the Republic’s bold advances. But like all fragile things, this wouldn’t last.

The Republic was brought to an end when, in 1936, the Spanish Civil War began after months of planning. Some factions of the military who opposed the ideals and methods of the Republic decided to take matters into their own hands and organized a mutiny in Melilla. This sublevation started in Melilla and spread like wildfire across the country. What began as a military rebellion grew into something far bloodier and violent, igniting a civil war that would tear the country apart for the next three years.

The lines were drawn: on one side, the Republican faction, fighting to preserve the Republic; on the other side, the Nationals, responsible for the mutiny. These armies fought across the Spanish geography, dividing the country, each claiming territory, each strengthening their hold on the different provinces.

But despite what most people might think, the combat wasn’t the most deadly partaker in this war, the Paseillos were. Josefa and Felisa, both locals in small towns, knew this process well. Especially Felisa, whose husband Santiago became an unwilling witness to one of these Paseillos. It was this moment that would change the course of his life and of those around him, triggering a set of events that would lead to his incarceration.

But the Spanish Civil War was something more than just a mere internal conflict: it became the prelude of something greater: the Second World War.

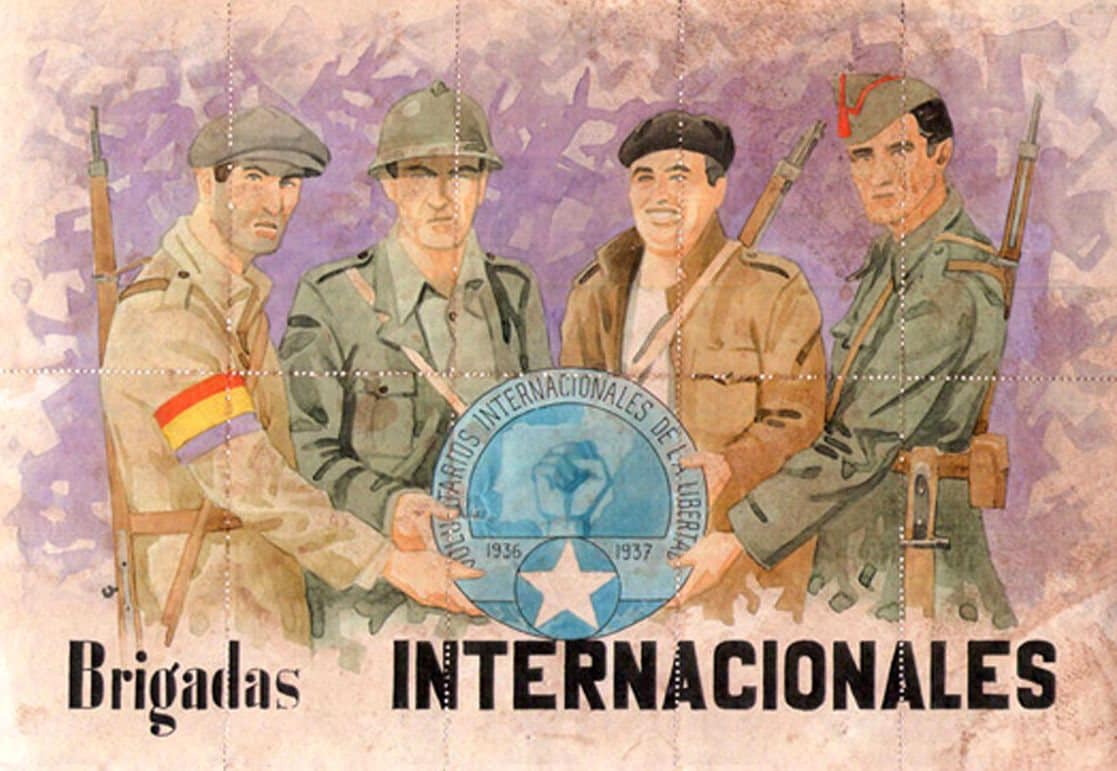

With the rise of Fascism all around Europe and tensions running high between the countries that would compose the Axis powers and the Allies during said war, all eyes turned to Spain and the fight that was ensuing. The war happening on Spanish soil wasn’t just a fight for the future of the country, but a stage where ideological battles of the world were being played out.

In this context, European leaders tried to avoid being pulled into another catastrophic war. In an effort to keep the peace in the continent for a bit longer, non-involvement pacts were signed. They pledged that no nation would directly interfere in the Spanish conflict. This was a desperate attempt to contain the spreading flames of war. Spain became the battleground, but Europe (and soon after the entire world) would pay the price.

Historical context

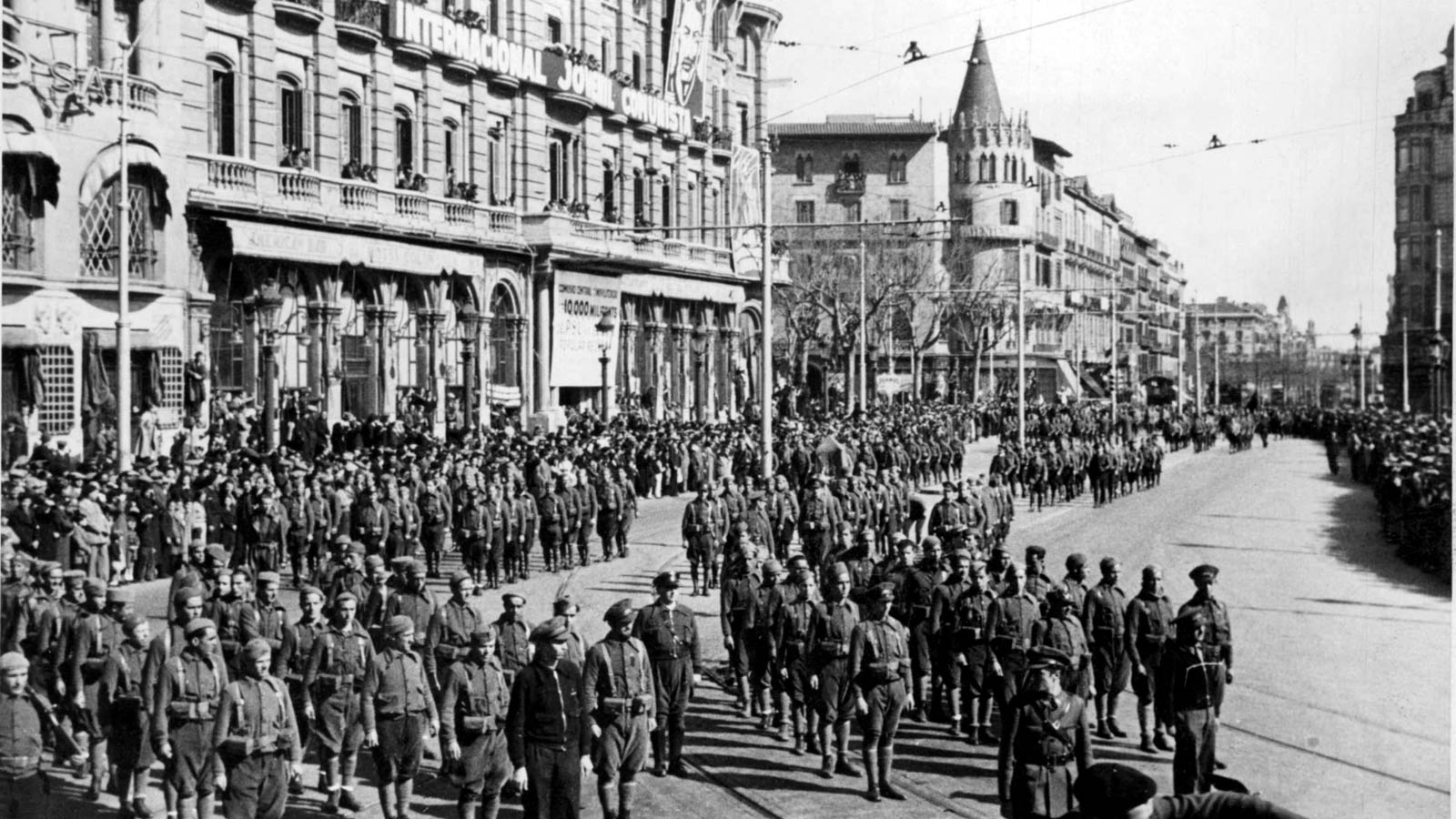

Picture of kids waiting to leave Spain after the Civil War. Retrieved from RTVE

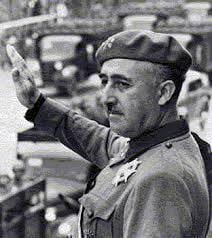

On April 1st, 1939, after three long years of fighting, the final war report would be signed by Francisco Franco. The ink, dark and final, sealed the fate of the nation: the defeat of the Republican band was clear and the victory belonged to the Nationals, marking the beginning of the Francoist dictatorship. The war was over, but the real battle, the struggle for Spain's soul, had just begun.

Picture of kids doing the fascist salute. Retrieved from RTVE

Echoes of Fear: The Silent Legacy of Franco’s Repression

The Francoist dictatorship lasted 36 years, from 1939 until Franco’s death, in 1975. This period of time is marked by a suffocating repression, a relentless grip on freedom and an economy crippled by autarchy. Perhaps, the most defining feature of this period of time was the glorification of Franco’s figure as Spain’s self-appointed savior, and the firm dominance of the Catholic Church.

The Church played a crucial role in this dictatorship. As Emilio Silva Barrera, journalist, sociologist, and one of the founders and president of the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory (ARMH), says:

For those who had sided with the Republic, either during the war or during democratic times, life became a nightmare. The supporters of this defeated cause were forced to either flee, or face the consequences of their political affiliations. Many of those who chose to escape and seek refuge in foreign lands kept fighting the battle from abroad: using the tools granted by a democracy that Spanish citizens didn’t enjoy anymore, they rallied, raised their voices and waged an ideological battle against the regime, hoping to end the dictatorship from abroad.

But for those who remained, the fight was far from over. For them, survival became a daily routine. Some, the maquis, decided to keep fighting. Others chose to try and live their life in peace, staying away from the fight and politics to try and save their lives. Yet, most wouldn’t be able to find this peace they so longed for. People like Manuel, politician for the Spanish Socialist and Workers’ Party (PSOE) during the Republic, had no choice but to endure the punishments of Franco’s regime. He was imprisoned and silenced for his ideals, and he became one of many whose lives were shaped by the political persecution of the regime.

Picture of Franco. Retrieved from RTVE

Picture of Franco with Spanish Bishop. Retrieved from Wikimedia

“[The Catholic Church] was an important tool of repression. During the sublevation and for 40 years it beat many people down. The abuses of the Church during Francoism are part of the Francoist memory”.

The progressive ideals of the Republic, built in the years before the war, were erased under Franco’s regime. Many advances of this previous time were swept away and replaced by a regime rooted in deeply misogynistic values, political repression and a highly conservative ideology tied to Catholicism. The republican dream of a free and democratic Spain seemed now like a distant memory, buried under the weight of a dictatorship that would choke the country for almost four decades.

Picture of people being punished during the dictatorship. Retrieved from Spanish's Ministery of Economy, Commerce & Business

When one gets hurt with a wound or a broken bone, it is always recommended to treat these as soon as possible. When mishandled, wounds will turn into ugly scars, and broken bones will never fully heal, the pain remaining for years to come will remind you of that bad fall or that moment of weakness. If we speak of emotional injuries, the same reasoning is applied and, although we might not see them, most times, these are the most painful of all.

The Amnesty law applied in Spain in 1977 could be the equivalent of putting a bandaid over a mutilated finger. Despite the intention being a good one, to heal and move on, it might do more damage than good.

Two years after Franco died, the Amnesty Law was passed. Its intention was clear: to forget the horrors of the past and move on to a brighter future, filled with hope, democratic values and freedom for all. Yet, for many, it meant that their suffering wouldn’t be acknowledged and that the crimes done to them would never be brought to justice.

Wounds of the past: about healing and keeping memories alive

“Democracy was obtained in exchange of impunity for the dictatorship”, says Pedro Alberto García Bilbao, doctor in sociology and president of the Forum for Memory of Guadalajara. “The dictatorship ends, followed by the Constitution of 1978, but the thing is that the previous regime isn’t considered illegal, and neither is the mutiny. No one was charged, there is no healing from this past in Spain (...) The freedoms that are achieved through the Constitution of 1978 have a price, and this price is that institutionally, some issues won’t be handled as they should”.

The Amnesty Law that served for the foundation of the current Spanish democracy established an impunity for all acts considered crimes that occurred during the war and the dictatorship, thus pardoning all authorities and agents that had committed crimes or violated human rights.

Despite the fact that the Amnesty Law was a necessary step for Spain’s transition into democracy, it was also a heavy burden. It helped to pave the way for the longed-for freedom, but it came at a cost that, even today, still haunts the country’s collective memory. This law opened the door for a democratic future but, at the same time, it closed a chapter that was yet unfinished, burying the truth underneath decades of silence.

When questioned about this, Pedro García states that:

In this sense, memory becomes a powerful tool through which we understand who we are and what we are capable of. For the descendants of the victims of the Civil War and Francoism, it allows them to trace their ancestors’ fates and finally lay them to rest.

For the victims of this tragic past and their families, amnesty meant a tragic erasure, a refusal to assign responsibility and confront the crimes of the past, leaving the wounds unhealed. With a lack of documents attributing accountability, the truth risks being lost in time. For them, the amnesty wasn’t the beginning of peace, but of an ongoing struggle for recognition. And so, as they struggle to keep the historic memory alive, they yearn for acknowledgment while history continues its relentless march forward.

“the democratic memory is the way societies remember the great occurrences of the past that get to us in the present and allow us to recognize ourselves throughout history as citizens that were capable of fighting for our freedom”.

Picture of kid celebrating the amnesty. Retrieved from Miguel Hernández University

Picture of the proclamation of the king. Retrieved from RTVE

Emilio Silva, journalist, sociologist & founder of the ARMH

Emilio Silva explores the critical role of memory in shaping history, emphasizing its power to uncover truths and challenge traditional historiographical perspectives.

This is specially relevant given his relationship with historic memory.

Pedro A. García, sociologist and president of the FEFFM

Pedro García reflects on the concept of historical memory, differentiating between memories of wars, and the focus on Francoist repression, highlighting the selective nature of what societies choose to remember.

Pedro García discusses the widespread impact of historical trauma in Spain, describing it as a collective issue affecting nearly three generations and extending into the present. He highlights the dual process of reconstructing personal and family histories while collectively rebuilding the nation’s historical narrative, a task made challenging by years of repression and silence.

Pedro A. García

Pedro A. García

Pedro García examines the Spanish transition to democracy, emphasizing how it was achieved by accepting the legality of the dictatorship in exchange for democratic freedoms, leaving the prior regime unprosecuted and unchallenged.

Emilio Silva

Here, Emilio Silva explores the struggles of Francoism’s victims, highlighting their lack of recognition, societal fear, and the enduring inequalities in how their pain is addressed by the state. It underscores the importance of justice and collective awareness in confronting Spain’s historical past. Then he emphasizes that forgiveness is a personal choice, not a state-imposed mandate.

Emilio Silva's grandfather, Emilio Silva Faba, was executed on October 16, 1936, along with thirteen others, at the entrance of Priaranza del Bierzo, where they were left in a ditch.

His whereabouts remained a mystery to his family until 2000, when Emilio Silva, driven by his desire to remember, decided to write a novel about the exiles from Villalibre de la Jurisdicción, his grandfather's village, who returned to Spain to dynamite the Valley of the Fallen. During a visit to the village, a chance encounter with a neighbor, Eugenio Marcos, changed the course of family history. Eugenio revealed the location of the mass grave where his grandfather’s remains were, leading to the first scientific exhumation of victims of Francoist repression in Spain.